Generating a form is always an intriguing process… but what about generating a set of rules that generate a form? Or even more intriguing, a form that generates itself?

There are many roots of the generative thinking, but there is no doubt that biology provided in the 19th and 20th century the fundamental ideas to comprehend the natural phenomena as the result of rule-based processes. We can cite here Darwin’s natural selection, Watson and Cricks’ discovery of the DNA structure and the seminal work of D’Arcy Thompson On Growth and Form. Along the 20th century, with the propagation of systemic theories and information technology, rule-based processes occupied an important role in art and design. Terms like “complexity” and “emergence”, research fields as “artificial life” or techniques such as “form-finding” or “evolutionary algorithms” permeate current production.

The idea of this post is to present an interesting branch of art that instead of maintaining a inspiration in biological processes, utilizes theses natural processes as the raw material for a generative art. Cyberneticians such as Gordon Pask were also interested in things like slime molds and ferrous sulphate solutions in the 1970s. Particularly, slime molds (and other molds) are interesting because they morph from unicellular entities into aggregate.

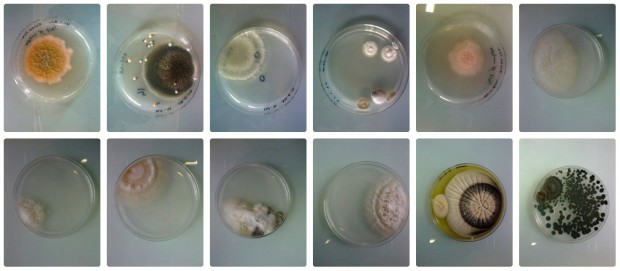

The project magical combination (and here, 2012-2014) by Antoine Bridier-Nahmias explores the visual characteristics of different molds. It is very interesting to have all these organisms growing and presenting different patterns. However, I believe that the emphasis on the pictures end up treating molds as static visual compositions, and hides its growth process and all the techniques behind the project. Of course, if the author adopted a critical discourse, this conflict with the logic of an growing organism could be seen as the exposure of the arbitrariness of an artistic image or even a critique about the privilege of human creativity in aesthetics.

There is another project that tries explicitly to register the growth of the molds and also to influence it. The Nexto biologic workshop ( and partners, 2014) was based on the use of programming and 3d-printers to simulate/generate a pattern upon which the slime mold would growth and adapt itself to. I believe this project does not have a huge visual impact, it did not took so long as the first and it also does not have a space to question the structure of the artistic field and aesthetic discourse. However, it has a fascinating characteristic. As it explicitly exposes human interference (it is a workshop) the results depart from the field of visual aesthetics to a kind of curiosity associated with the development of simulations and (at some level) even with board / strategy games.